The 1890 blackballing that spawned a $60 million revenge palace on Fifth Avenue

In the winter of 1890, John Pierpont Morgan — the most powerful banker in America, a man who would later bail out the entire U.S. Treasury — received devastating news from the Union Club of New York.

His friend had been rejected.

The Union Club, founded in 1836 and known as the “Mother of Clubs,” had blackballed John King, president of the Erie Railroad, despite Morgan personally sponsoring his membership. The same night, they also rejected Dr. William Seward Webb, president of the Wagner Palace Car Company and brother-in-law to Frederick Vanderbilt — sponsored by William K. Vanderbilt himself.

The rejections were humiliating. Local newspapers routinely published the names of blackballed applicants, exposing both the rejected men and their sponsors to public ridicule. For Morgan — a titan who controlled one-sixth of America’s railways — this was intolerable.

He didn’t beg for reconsideration. He didn’t lobby the board. He quit.

And then he built something better.

The Dinner That Changed Fifth Avenue

On February 20, 1891, Morgan summoned 25 of the Gilded Age’s most powerful men to dinner at the Knickerbocker Club. The guest list read like a roster of American empire: Vanderbilts, Roosevelts, Goelets, Iselins, Whitneys.

His friend William Watts Sherman drafted a constitution on the spot. They considered names: “Millionaires’ Club,” “Park Club,” “the Spectators.” They settled on the Metropolitan Club. Morgan was elected first president.

His instructions to architect Stanford White were legendary:

“Build me a club fit for gentlemen. Forget the expense.”

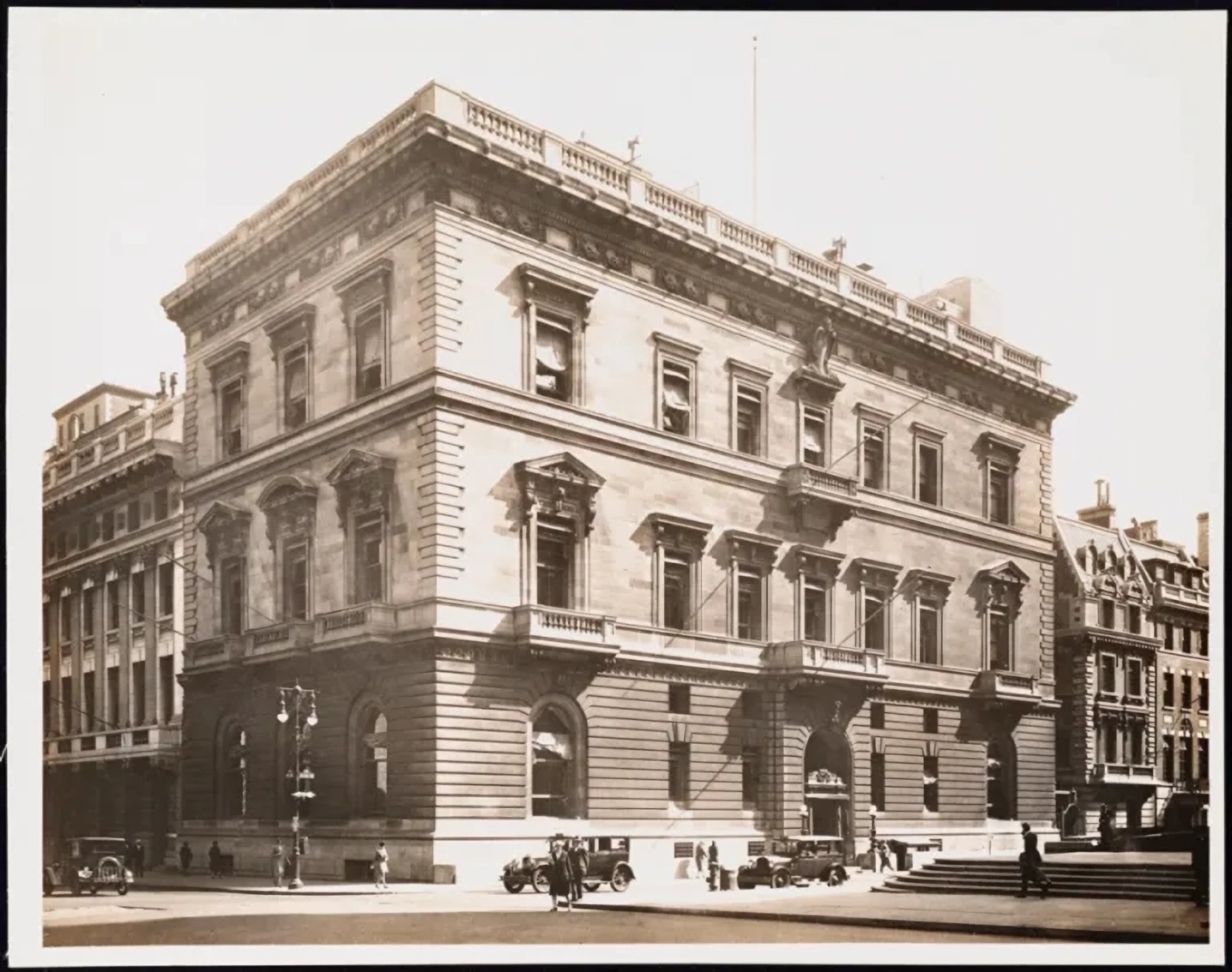

White — himself a charter member, along with his partners Charles McKim and William Mead — delivered exactly that. He designed an Italian Renaissance palazzo that would dominate the corner of Fifth Avenue and 60th Street, directly facing Central Park. The entrance was deliberately placed on 60th Street, turning the club’s shoulder to Fifth Avenue — only massive windows faced the street, so that those outside could look in and see what they were missing.

Metropolitan Club grand staircase. Image by Susan Shek, Susan Shek Photography.

A Palace of Revenge

The Metropolitan Club opened in 1894 after three years of construction, labor strikes, and Morgan’s obsessive attention to every detail — down to the carpets.

The final cost: $1,777,480.20

Adjusted for inflation, that’s approximately $60 million — for a clubhouse.

The New York Times declared it “a clubhouse the equal of which does not exist in this country or in any other.” When Stanford White died in 1906, the paper eulogized him by calling the Metropolitan “the handsomest and most complete clubhouse in the world.”

The building’s features were deliberately excessive:

– Numidian marble throughout the vestibules and main rooms

– Ceiling murals by Edward E. Simmons

– A dazzling double staircase that Town and Country would later say other clubs “envied”

– Cherry, mahogany, and oak woodwork with bronze sconces and iron handrails

– A courtyard modeled on Italian Renaissance palazzos

When you walked in, you understood immediately: this was not the Union Club. This was what money could build when it was angry.

The Ultimate Insult

The Metropolitan Club’s founding roster was a deliberate rebuke. The Vanderbilts, Roosevelts, Goelets, and Whitneys had all been Union Club members. Now they were something else — founders of a rival institution designed to make the Union look provincial.

And John King? Morgan’s blackballed friend, the man whose rejection sparked it all?

He was invited as a charter member.

The Union Club, suddenly anxious, proposed a merger in mid-1893. Their members voted it down — too proud to admit defeat. But the damage was done. The Metropolitan had announced to New York society that the old guard no longer controlled the gates. If they wouldn’t let you in, you could build your own palace.

The Man Behind the Myth

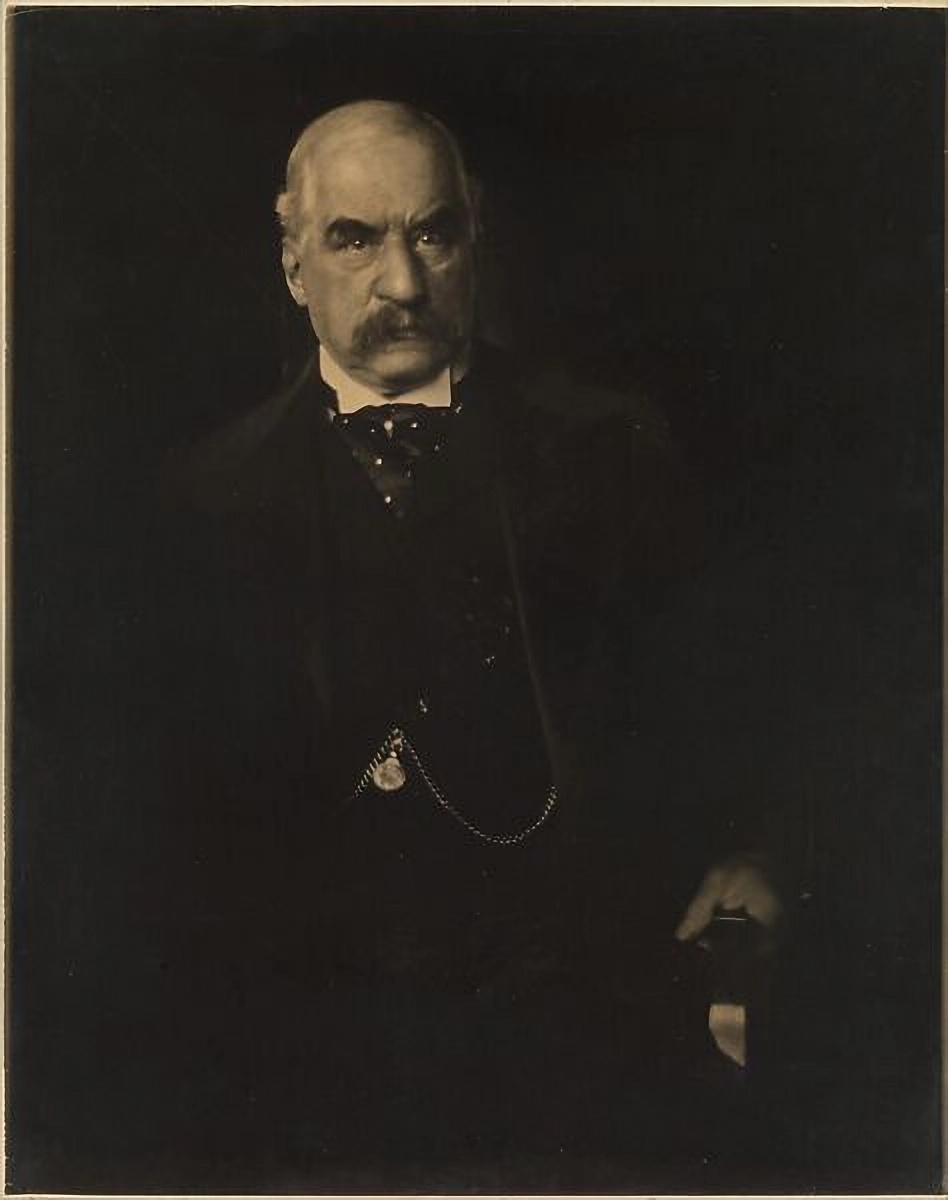

Understanding Morgan’s fury requires understanding Morgan himself.

He was, by 1890, among the most powerful men on earth. His bank financed railroads, steel mills, and eventually General Electric. In 1895, he would loan $60 million to rescue the U.S. government’s gold reserves. He functioned as a one-man Federal Reserve until the actual Federal Reserve was created — the year he died.

But Morgan was also deeply insecure about one thing: his appearance.

He suffered from rhinophyma, a chronic skin condition that left him with what biographers described as a “hideously bulbous purple nose.” He hated being photographed. When Edward Steichen captured him in 1903 — in what became one of the most famous portraits in American history — Morgan initially tore up the proof in disgust.

The portrait shows Morgan glaring at the camera, a flash of light on the chair arm creating the illusion of a dagger in his hand. It became the defining image of Gilded Age capitalism: ruthless, formidable, dangerous.

But behind that glare was a man who burned his personal letters to protect his privacy, who avoided public speaking, who collected art with obsessive passion. A man who, when his friend was publicly humiliated by a club, didn’t shrug it off.

He took it personally. And he responded with $60 million worth of marble.

The Legacy: Why This Story Still Matters

The Metropolitan Club stands today at 1 East 60th Street, a New York City landmark still operating as a private club. Its interiors remain largely unchanged — the same murals, the same marble, the same double staircase that announced Morgan’s arrival 130 years ago.

But the story matters beyond architecture. It established a template that defines private clubs to this day:

Exclusivity creates its own opposition. The Union Club’s blackball system — designed to maintain purity — produced the very rival that would overshadow it. Every time a club rejects someone with resources and ambition, it risks creating competition.

The rejected don’t always disappear. John King, the railroad president deemed unworthy of the Union Club, became a charter member of the most lavish clubhouse in American history. His rejection became his credential.

Money, when insulted, builds monuments. Morgan could have sulked, could have lobbied, could have quietly joined another club. Instead, he spent what would be $60 million today to prove a point. The Metropolitan Club isn’t just a building — it’s a permanent record of what happens when you embarrass the wrong person.

Money, when insulted, builds monuments. Morgan could have sulked, could have lobbied, could have quietly joined another club. Instead, he spent what would be $60 million today to prove a point. The Metropolitan Club isn’t just a building — it’s a permanent record of what happens when you embarrass the wrong person.

Metropolitan Club library. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Club.

The Modern Echo

Today’s private club boom carries echoes of 1891.

When Scott Sartiano opened Zero Bond in 2020, he wasn’t building for old money. He was building for founders, athletes, entertainers — people who didn’t need the Union Club’s approval. When Jennie Enterprise launched the Core Club in 2005 with no dress code and no rules, she was explicitly rejecting the Gilded Age model.

The pattern repeats: an established order gets too comfortable with its gatekeeping, and someone with resources builds something new. The names change — Morgan to Sartiano, the Union Club to whatever institution gets too smug — but the dynamic remains.

Exclusivity, it turns out, is never permanent. It just waits for someone wealthy enough, and angry enough, to prove it wrong.

The Metropolitan Club remains open for private events. The Union Club, for its part, is still operating — still exclusive, still at the corner of 69th and Park. Whether its members discuss the 1890 incident that spawned their greatest rival is unknown. Some rejections, after all, are better forgotten.